The Theology of Outrage

Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Columbia

April 15, 2018

Rev. Jeff Liebmann

Opening Words

from Faraday as a Discoverer (1868) “Points of Character” by John Tyndall

Michael Faraday was one of history’s greatest scientists. His work in electromagnetism, and the popularization of terms

the popularization of terms![]() such as “anode”, “cathode”, “electrode” and “ion” led to the eventual practical use of electricity in technology.

such as “anode”, “cathode”, “electrode” and “ion” led to the eventual practical use of electricity in technology.

Physicist John Tyndall one said. “We have heard much of Faraday’s gentleness and sweetness and tenderness. It is all true, but it is very incomplete. You cannot resolve a powerful nature into these elements, and Faraday’s character would have been less admirable than it was had it not embraced forces and tendencies to which the silky adjectives “gentle” and “tender” would by no means apply. Underneath his sweetness and gentleness was the heat of a volcano. He was a man of excitable and fiery nature; but through high self-discipline he had converted the fire into a central glow and motive power of life, instead of permitting it to waste itself in useless passion. Faraday…completely ruled his own spirit, and thus, though he took no cities, he captivated all hearts.

Story for All Ages

Nelson Mandela and the Sparrow

Back when I was your age, many people were suffering in a country called South Africa. Most of the people living in South Africa had dark skin. But, people with light skin held all the positions of power and owned all of the property and businesses. The blacks had few rights and police regularly beat and arrested them. This system of government was called Apartheid.

Nelson Mandela was a leader of a resistance group trying to create fairer laws in South Africa. He led many protests and other acts of nonviolence, but nothing worked. Mandela grew angrier and angrier. Forced to hide from the police, Mandela considered shifting his movement toward violent tactics.

Hiding out on a farm near Johannesburg with other members of the resistance movement, Mandela began plotting an armed struggle against the Apartheid regime. But the only gun Mandela had was an old air rifle he used for target practice.

Years later, Mandela wrote in his autobiography, “One day, I was on the front lawn of the property and aimed the gun at a sparrow perched high in a tree.” He hit the bird and he was about to boast about it when his friend’s five-year-old son, with tears in his eyes, asked Mandela, “Why did you kill that bird? Its mother will be sad.”

Mandela wrote, “My mood immediately shifted from one of pride to shame. I felt that this small boy had far more humanity than I did.”

Mandela remained angry for a very long time. He was arrested and spent many years in prison. Eventually, however, the Apartheid government realized that changes had to be made, and they turned to Mandela to help end the violence and to help create a just nation.

Sermon – The Theology of Outrage

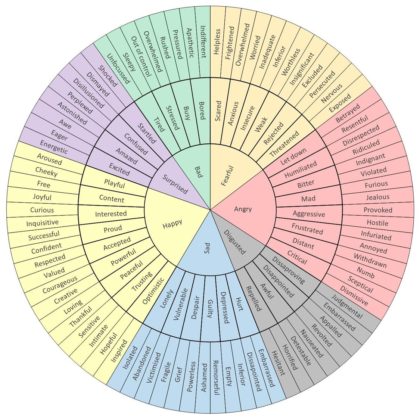

During my time as a hospital chaplain, the clinical pastoral coordinator shared a device well known to most counselors, therapists, and social workers called the Emotion or Feeling Wheel. Whenever he asked, “How are you feeling?” a typical response of saying “good” or “fine” was not acceptable. Only an emotion from this wheel served as a satisfactory response.

This task challenges one to fully experience feelings and to express them. Many people find this exercise daunting because it opens us to new vulnerabilities and areas of self-awareness. Speaking aloud the label of a felt emotion forces you to actually deal with that emotion. When that emotion is a particularly strong one that stirs your blood, that process of discernment can be enormously painful, but educational.

While serving my previous congregation in Michigan, I wrote almost 200 print and online editorials for the Midland Daily News. Those of you who read online newspaper articles likely know about the kinds of comments they receive. Many supported my positions. Some disagreed, but shared some opposing reason and logic. Then, there were the trolls.

Internet trolls are individuals with extreme social and political views fond of using intimidation tactics in the mostly unregulated public forum to shout down opposition. As one might imagine, I quickly developed a devout troll following.

I started writing editorials in Michigan right after the Newtown massacre in December 2012. After voicing my views on guns, the trolls descended with hundreds of comments. I did not respond to the merely insulting comments, believing that remaining above the name calling and personal denigration would keep the conversation above the playground level. But, truth be told, even when the source of an insult is not one deserving of any respect, an insult still stings just a little.

I responded to any attempt at presenting a legitimate argument against my positions. I defended this expenditure of time as honing my own skills of debate and even possibly changing some minds. Little did I know, however, that by engaging with the trolls, I had fallen down a rabbit hole.

The leader of a local hate group, Yahweh’s Truth, posted a video rant excoriating me as a Communist Jew and a traitor to the United States. I found my name mentioned in Stormfront, a white supremacist, Neo-Nazi online forum. Several local citizens made it a point to write letters to the editor questioning my credentials as a member of the clergy.

But my most dedicated follower was the head of the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. He and I exchanged hundreds of comments over the years. His carefully veiled threats were always just vague enough to elude prosecution. I reported him to the police several times anyway just to ensure that a record of the attacks was on file in case he ever followed through.

He carried the assaults beyond the Newspaper’s online page. He trolled my Facebook page often, as well as that of the church. On a few occasions, he created fake Facebook identities and then slammed my accounts with dozens of vile memes and revolting photographs. Of course, all the reporting to Facebook accomplished nothing.

His crowning tribute came when he purchased my name as a web domain and created a site warning people of my evil teachings. The last iteration is an abbreviated alarm to the people of South Carolina that I was the Anti-Christ and to flee from my preaching.

In my life, I have always tried to see the best in people. I try my best to assume good intentions and to see things from others’ point of view. Naively perhaps in retrospect, I took this zealot on as a crusade. I never really thought I would convert him over to my point of view, but I wanted to reach others who might be influenced by his writings and show them that hatred and fascism only breed violence, oppression, and misery.

Week after week, I would write articles and monitor the comments. Sometimes, comments would come from far-flung places, so I knew a network of trolls shared my editorials. But, I always took the time specially to refute false Biblical citations, and arguments riddled with logical fallacies. People in town would stop me in the grocery store and thank me for taking on this task, which did encourage me. In time, however, I began to pay the price for my diligence.

from far-flung places, so I knew a network of trolls shared my editorials. But, I always took the time specially to refute false Biblical citations, and arguments riddled with logical fallacies. People in town would stop me in the grocery store and thank me for taking on this task, which did encourage me. In time, however, I began to pay the price for my diligence.

With each insult, each accusation, each attack against underprivileged people, I got a tiny bit angrier. After many months of these exchanges, I found myself growing weary and emotionally drained. I lost my temper a few times in exchanges, but the real impact was the rage I felt brought on by these racist, misogynistic, homophobic, xenophobic, and other fear and hate-based comments began consuming me.

The more virulent the attack, the harder I felt compelled to answer back. Indignant rage sometimes took over and I imagined people out there following these conversations who were glad to know that someone was standing up for progressive morals.

The toll on my soul, however, finally grew too great. Eventually, I accepted that I was pouring my emotional energy into a bottomless pit, and that the price my spirit paid far outweighed any potential for good. But, what to do with the rage? How could I dispose of this vat of toxic emotion?

First, I had to remove myself from the conversations and accept the fact that my reasoned responses would never wear down the trolls. For instance, our congregation in Montreal was finally forced to expel a member for his disruptive and abusive behavior. This fellow has spent the last 20 years trolling any Unitarian Universalist minister with an online presence. At first, he seems reasonable and encourages intelligent discourse. But, then the troll kicks in. Many of my colleagues share my experience with this very dedicated enemy of our denomination.

But stepping back from these online conversations saddened me. I had grown used to feeling exposed and vulnerable, but now I felt resigned to a failure of sorts. I realized, though, that in my zeal to lead my congregation and change the world, I had moved so far in front of them that they were unable to keep pace and share the burden.

Next, I curbed my impatience. I fought the urge to respond immediately to comments. I committed myself to the task of educating gradually and slowly building consensus on the need for change and awareness of ways to accomplish it. I became less reactive, channeling that rage into sermons and writings aimed less at expressing my own anger and more at encouraging others to express their own in productive ways.

Lastly, I let go. This step challenged me greatly. But I realized that the constant drive to be the best, to win every argument, derives a great deal from the privilege I was fortunate enough to be born with. Having the last word is a luxury reserved for those able to absorb the consequences and with the support network able to handle the system shocks. Using up emotional capital on nonproductive battles only diverted me from real goals of social change and developing real solutions to the problems plaguing those I had sworn to stand beside in their struggles.

Lastly, I let go. This step challenged me greatly. But I realized that the constant drive to be the best, to win every argument, derives a great deal from the privilege I was fortunate enough to be born with. Having the last word is a luxury reserved for those able to absorb the consequences and with the support network able to handle the system shocks. Using up emotional capital on nonproductive battles only diverted me from real goals of social change and developing real solutions to the problems plaguing those I had sworn to stand beside in their struggles.

Today, we face new challenges. We live in a country teetering on the brink of fascism and nuclear war. I am not alone in my concern. In recent months, I have quietly worked on the Ministerial Leadership Network of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee. I talk with other ministers fearful of the threats to our democracy and especially to vulnerable populations. Some of us believe that we stand perilously close to times like those when Martha and Waitstill Sharp went to Czechoslovakia to help refugees fleeing Nazi tyranny.

I shared with them my participation in the Civil Defense Corps, a fledgling group devoting itself to protecting minorities in our nation from the ravages of totalitarianism. The shock we feel when we see ICE raids, hear anti-Muslim rhetoric from our highest officials, and feel powerless to stem the tide of violence and bigotry in our country lead me to the conclusion that we must begin planning for the unthinkable. I will be discussing this work next Sunday during the Social Action Committee meeting after the worship service, and I invite anyone interested to attend.

I was proud to host the Moral Fusion Direct Action training here yesterday sponsored by the Poor People’s Campaign. More than 50 people attended, attesting to the level of concern shared by so many of the threat facing our neighbors dealing with the terrible grip of poverty, attacks on voting rights, victimization of the most helpless, and the immorality of our national priorities. I encourage everyone to learn more about this effort.

Jody and I are honored to work with local college and high school students on the March for Our  Lives, which just organized one of the biggest marches in Columbia’s history calling for sensible gun reforms. I was so proud to see 70 of you attend the march.

Lives, which just organized one of the biggest marches in Columbia’s history calling for sensible gun reforms. I was so proud to see 70 of you attend the march.

The time for our message, for our principles of Unitarian Universalism to rise is now. We have felt disappointment, confusion, and anxiety. Many of us have raged against the rising tide of injustice here in South Carolina and across our nation.

The challenge before us is to take that rage, that inferno of passion for justice and change, and resist to temptation to immolate ourselves on its pyre. Instead, we must find a way to transform rage into resolve, anger into action, and fear into freedom.

Prayerful Reflection

Spirit of life and love, join us in a shared moment of peaceful reflection and prayer.

None of the work lying ahead of us is possible if our own foundation as a community of searchers and believers cannot bear the weight of our goals. In the past year, many of us have struggled with feelings caused by the pain inflicted on the underprivileged in our society, and the very real threats posed to immigrants, people of color, women, LGBT folk, and the poor. Unfortunately, those feelings can manifest itself in harmful ways on ourselves and on our church relationships.

When you called me to serve as your minister last year, I was impressed by your covenant. You clearly crafted a document out of experience and a sincere desire to rise above baser instincts to create a church that would speak to many seekers.

Welcoming new members offers us the opportunity to review this document, this promise we make to each other again. When people in our community feel unheard, it is up to each of us to elevate their words into the conversation. When people feel victimized by rumor, it is up to each of us to affirm our commitment to the free and responsible search for truth and meaning.

When people feel unappreciated, it is up to each of us to respect their unique gifts and express our gratitude to all acts of stewardship. When people feel rejected and hurt, it is up to us to find solutions and resolve disagreements. If a woman feels vulnerable or unsafe here, then it is up to all of our men to check their privilege and change their behaviors. If anyone feels ignored, then it is up to all of us with power and influence to stop and listen. And when someone feels frustrated and angry, it is up to all of us to find ways to help them directly address the causes of their pain, to help us all avoid the fall into the chasm of despair.

None of us is innocent, and I am no exception. But I promise – that is what a covenant is, a promise – I promise to always do my best to listen to your concerns, and to do everything I can to help you make this congregation accepting and responsive; a safe place to experience sadness and joy, surprise and anxiety, even to feel angry, and to share those feelings in a healthy and productive way.

Our Living Tradition is never a finished product. We can always do better; we can always be better; we can always do more to build a better and beloved community.

Blessed be. Amen. Let it be so.

Closing Words

By Mahatma Gandhi

I have learnt through bitter experience the one supreme lesson to conserve my anger, and as heat conserved is transmuted into energy, even so our anger controlled can be transmuted into a power which can move the world.

Our Covenant

The Way We Are With Each Other

- We will make ours a positive, welcoming environment — one that includes the diverse perspectives of our spiritual community and builds a sense of connectedness.

- We will practice direct communication in all facets of UUFC life, using the power of our words to work toward solutions rather than additional problems.

- We will refrain from spreading hearsay.

- We will nurture each other’s spiritual and personal growth by entering into conversations and interactions with compassion, deep listening, and respect for differences of opinion without judgment.

- We will value and express appreciation for each contribution, whether it is time, money or effort.

- We will acknowledge conflicts, address them openly and honestly, and resolve them as close to their source as possible, using mediation if necessary.

- We will practice forgiving each other and ourselves.

Topics: theology